Let Go (Of Something)

- Paul Weinfield

- Sep 19

- 2 min read

In Camus’ novel, The Fall, the narrator recalls a man who sacrificed everything for a woman, only to realize two decades later that he’d never loved her. “He had been bored,” Camus writes. “Bored like most people. Hence he had made, out of whole cloth, a life full of complications and drama.”

So much of our striving is an attempt to fill an emptiness we’d rather not face. We think the problem is that we need to try harder — to fix our flaws, please others, be better people. But all too often, the real problem is that our energy goes not into reality but into thought-worlds we construct in order to avoid reality.

We all do this. Maybe it’s the drama of jealousy, in which checking your partner’s phone seems like the issue but really masks a deeper fear of intimacy. Maybe it’s the drama of perfectionism, in which working yet another self-help program seems like the issue but really masks a deeper refusal to accept yourself.

Dramas all share three traits. First, they’re cyclical: the roles we play in them go back to childhood, even previous generations. Second, they’re distractions: the “problem” is a way of avoiding the real problem. Finally, they’re futile: no matter how much we work on the drama, it never turns out differently or brings lasting happiness.

And so our task, as the Buddha taught, isn’t to wrestle harder with the drama, but to see it and let it go. To notice the mental loops, name them, and release them. Meditation gives us a fertile space to develop this skill in real time.

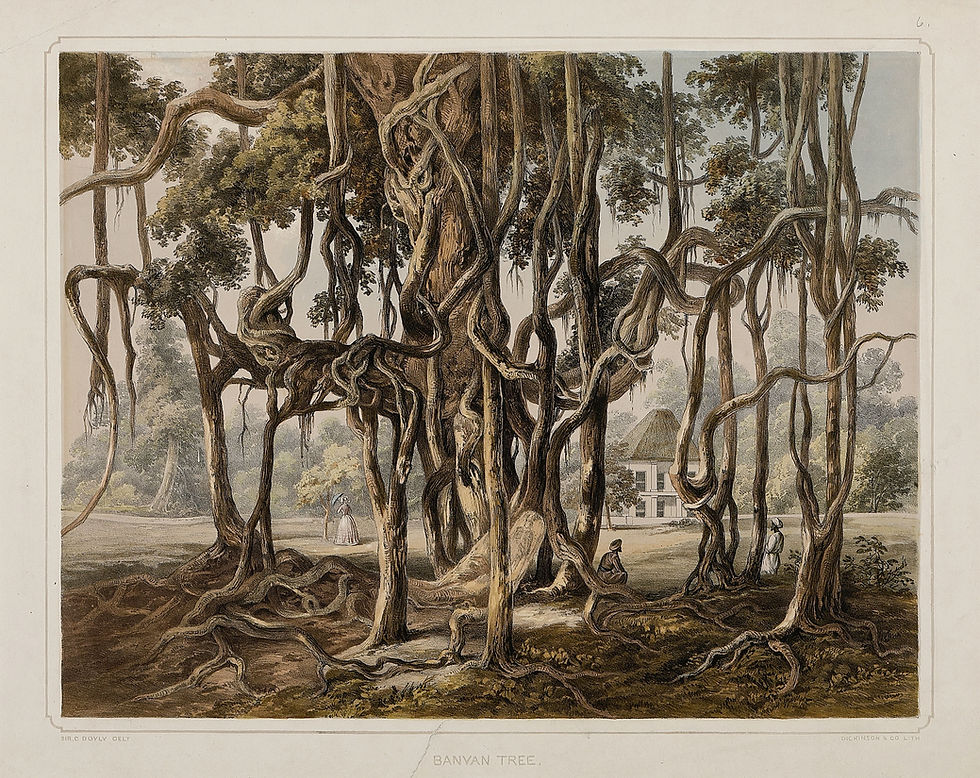

Rilke once said that holding on is easy but letting go is hard. That’s only partly true: letting go all at once may be hard. But like a tangled ball of yarn that can’t be undone with one tug yet can be patiently loosened, there’s always something you can release: a thought, a perception, a gripping in your body, a tightness in your breath. Just let go of something. You really can.

Comments